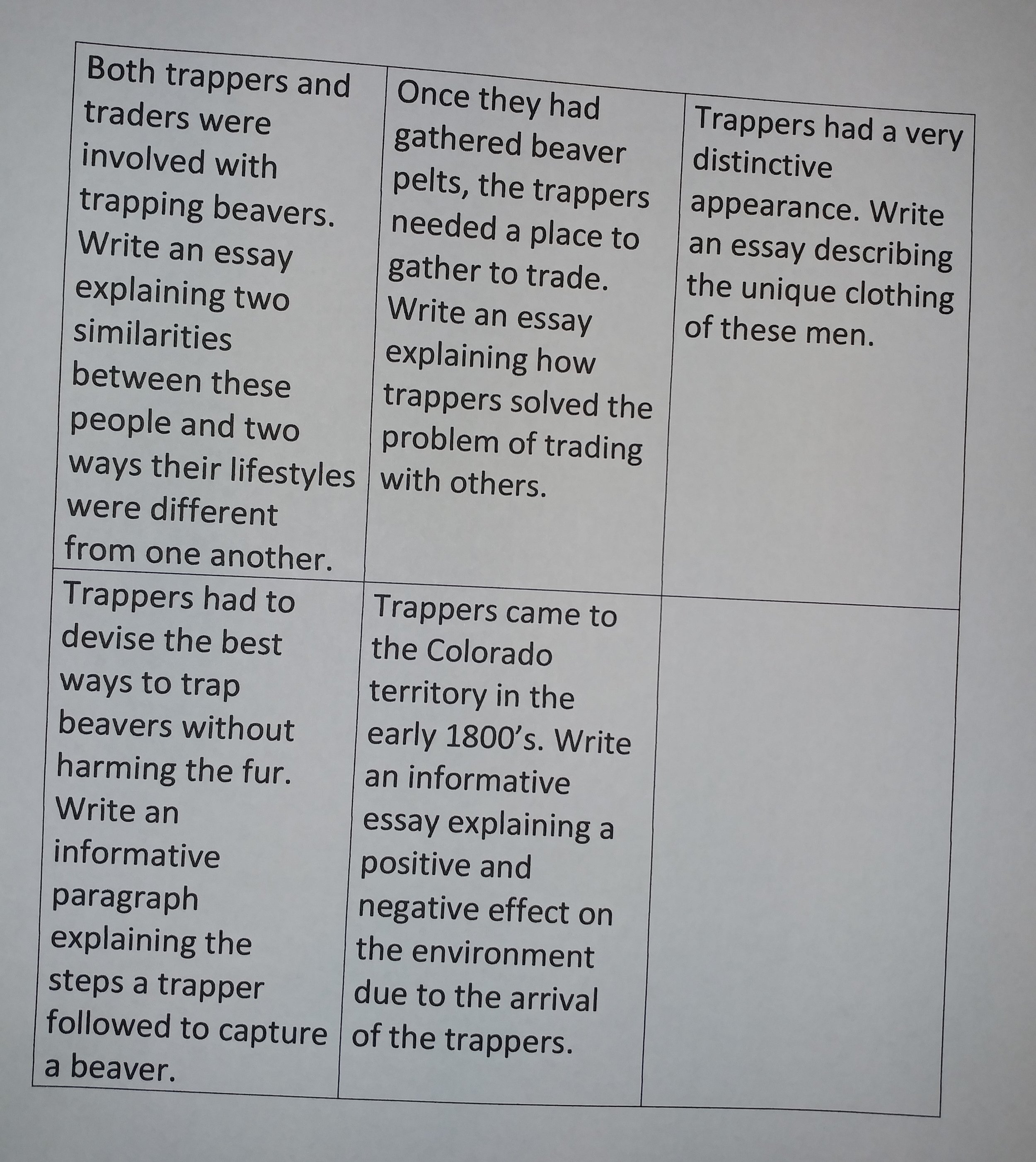

Writing an opinion essay is an expectation of all elementary students. Opinion writing is also a very effective genre to use when teaching students the different parts of a written essay: planning, topic sentences, big ideas, details, and conclusions. However, it can be challenging for teachers to engage students in this genre for an extended period of time. Having students write about their favorite restaurant, animal, or dessert lesson after lesson becomes redundant. While this is an effective way to introduce opinion writing to students, neither teachers nor students want to write about one favorite thing after another.

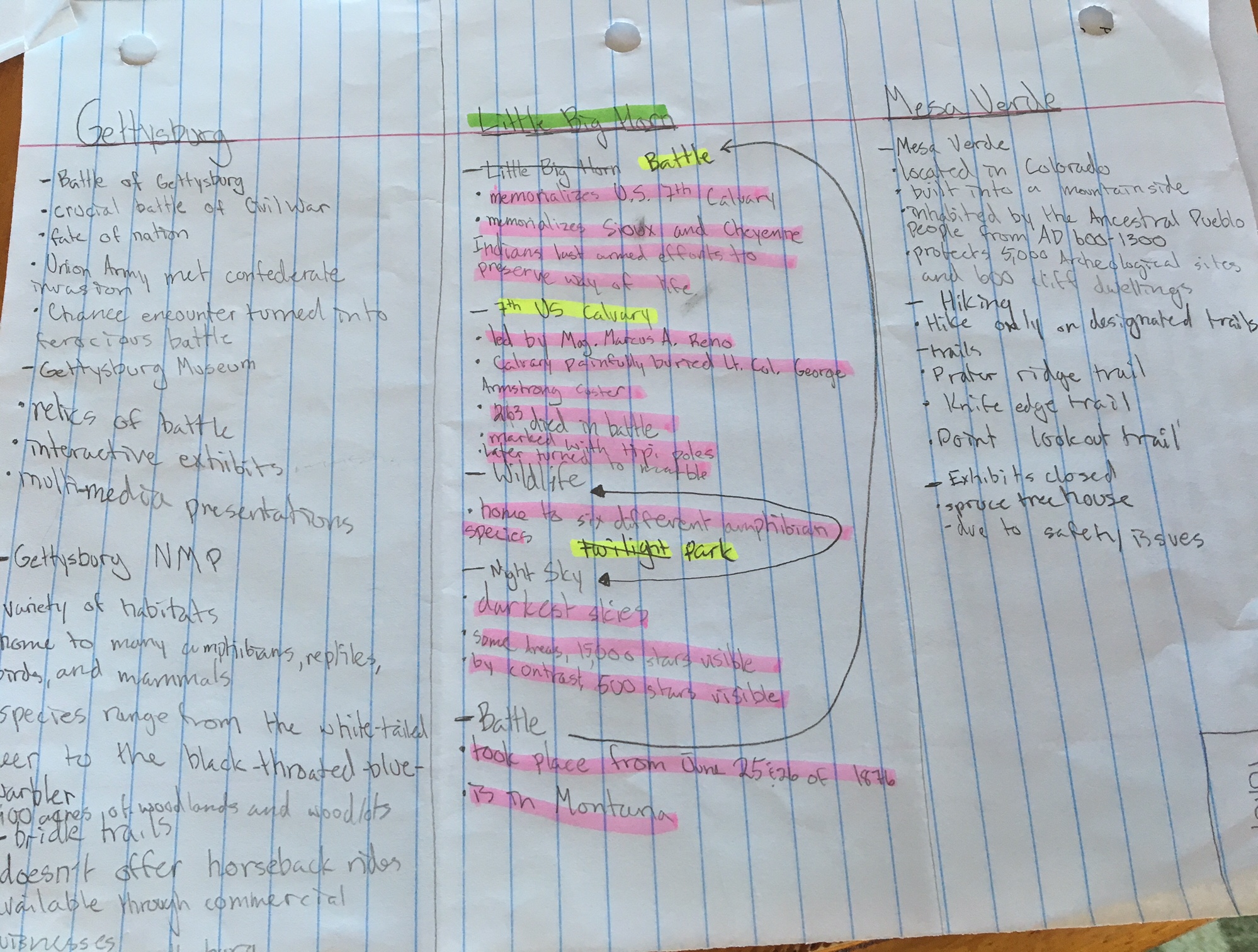

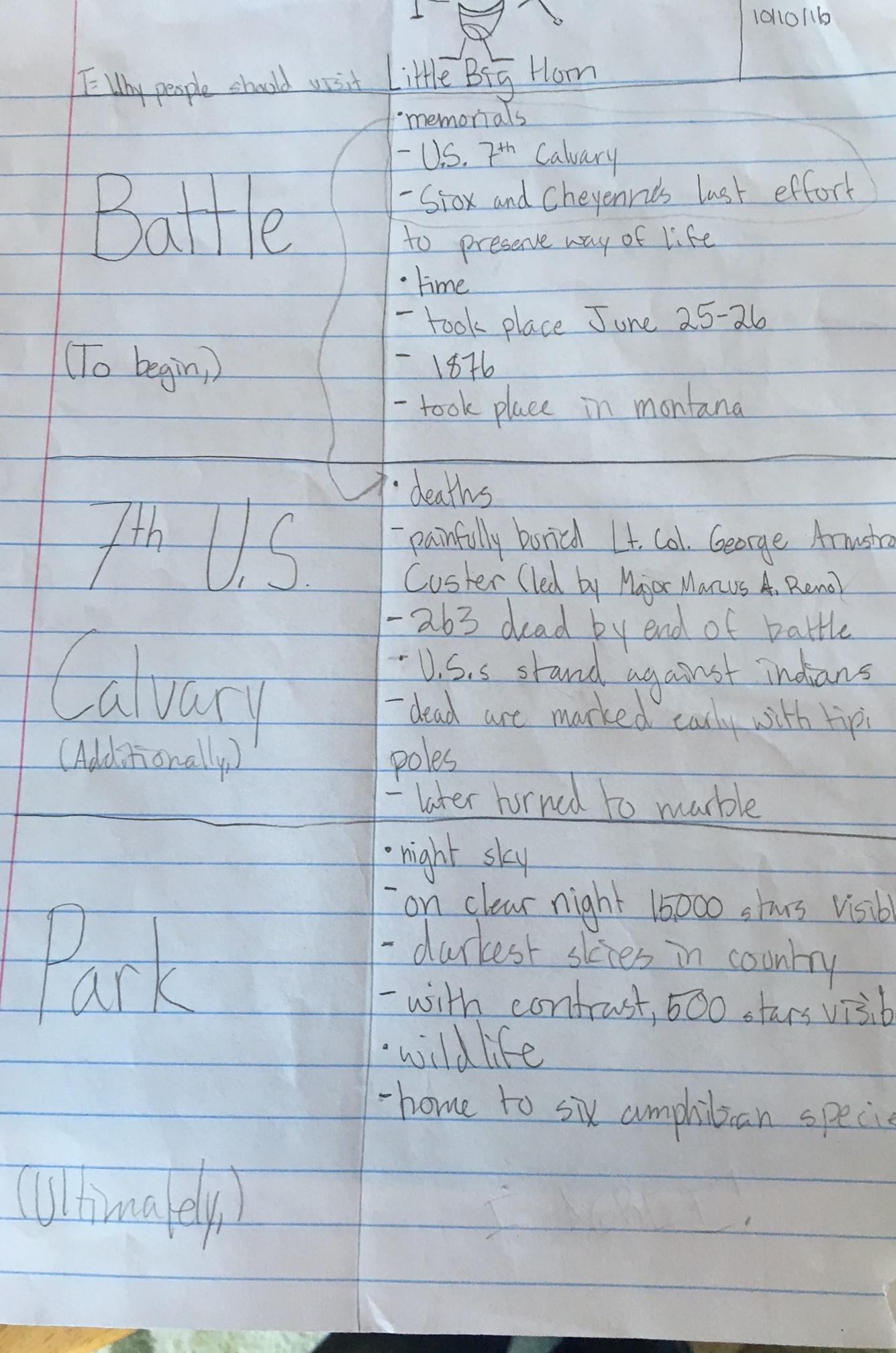

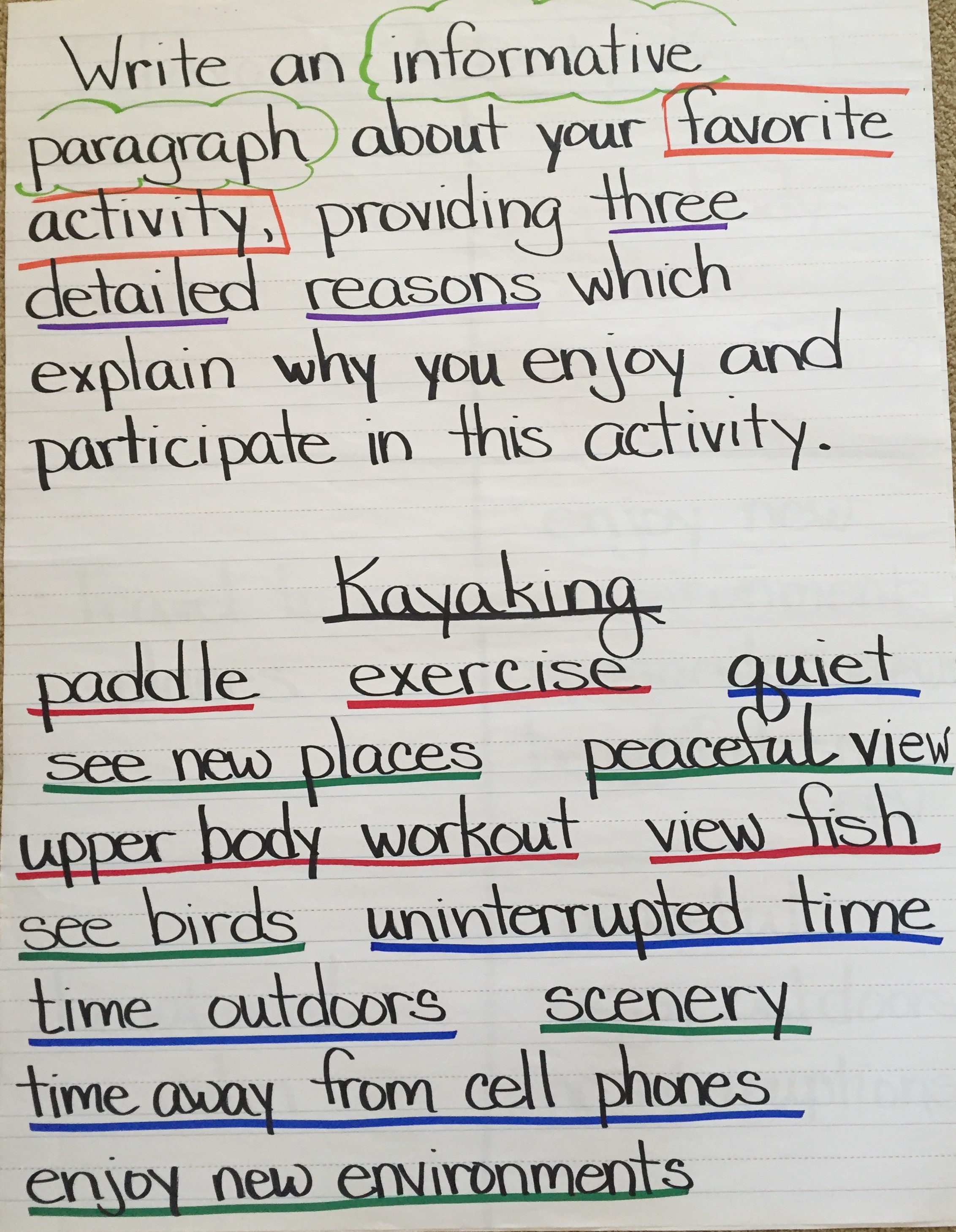

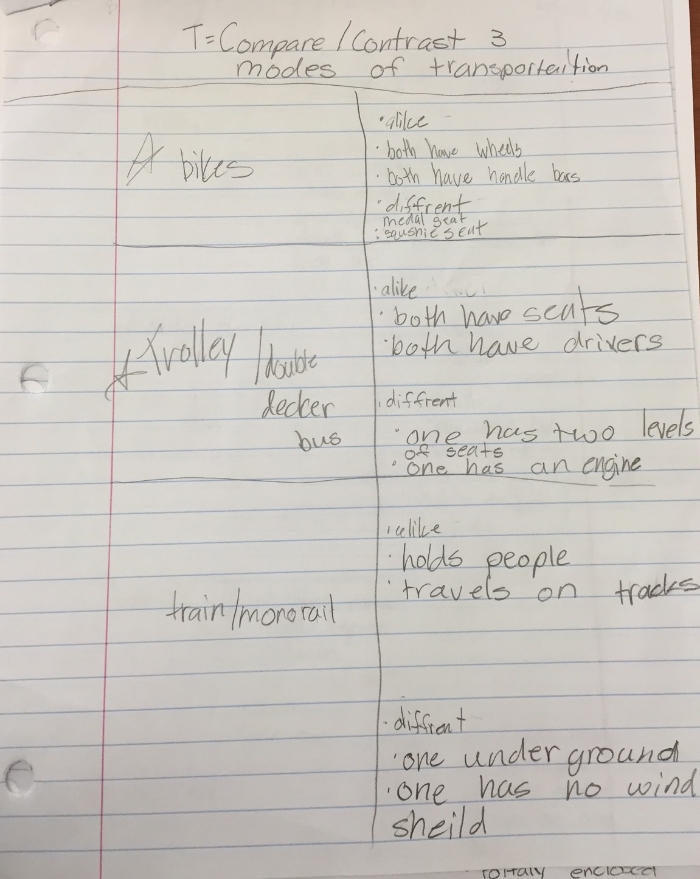

Additionally, teachers have an extensive amount of curriculum to cover in a year. As you teach opinion writing, consider writing prompts which reflect curriculum and events in your classroom. Students will be learning and practicing the parts of an essay while responding to actual classroom situations.

Examples:

Our class has earned a reward for great behavior. Think about what you would like our class to do to celebrate. The two choices are having a “wear pajamas to school” or “go out for an extra recess.” Write a Team Complete Sentence explaining which choice you like best. Include a reason you made this choice.

At our school, we are only allowed to have fish as class pets. Write an essay explaining whether or not we should get an aquarium for our classroom. Include two reasons to support your opinion.

We have just finished reading Charlotte’s Web. Would you recommend I read this book aloud to next year’s third graders? Write an essay explaining whether I should or should not read this book for next year’s class. Include two reasons to support your opinion.

Our class has been studying the planets. Imagine you have been given an opportunity to travel to one of the planets. Write an essay describing which planet you would choose to visit. Include reasons why you chose this planet to visit.

The PTA wants to purchase a new piece of playground equipment. They are deciding between a tube slide, a platform swing, and monkey bars. Think about which piece of equipment you would like to have in the playground. Write an essay explaining why you believe the PTA should purchase the equipment you chose. Include reasons to support your opinion.

We have been learning about rural and urban areas. You can choose to vacation in an urban area or a rural area. Write an essay describing the area you would choose to spend your vacation. Include two activities you would like to do in the area you chose.

The school administration is deciding the schedule for school lunch and recess. They are deciding whether students should go to recess and then eat lunch or eat lunch and then go to recess. Think about which schedule you prefer. Write an essay explaining which schedule you would prefer and why it is beneficial to students.

In school, students are asked to walk single file in a line whenever they are in the hallway. Do you think this is a necessary rule for fifth graders? Write an essay, explaining whether or not you believe older students need to walk in a single file line. Support your opinion with reasons.

At the school library you are allowed to check out one book at a time. The librarian is considering changing this rule. Think how many books you believe students should be able to check out at a time. Write an essay expressing your opinion. Include reasons to support your point of view.

Opinion writing doesn’t have to just be about a student’s “favorite” something. Finding ways to incorporate the genre within your curriculum or current events helps students’ motivation and enthusiasm on a topic.